In 2003, the government of Kenya instituted a free primary education for all program, and then did the same for secondary education in 2008. As a result, nearly three million more students were enrolled in primary school in 2012 than in 2003 and the number of schools has grown by 7,000. Between 2003 and 2012, the secondary gross enrollment ratio increased from 43 percent to 67 percent, as graduates from the new free primary program moved their way through the system. More recently, the impact of the 2003 education for all program has been seen at the university level, where enrollment numbers have skyrocketed, more than doubling between 2012 and 2014 as the initial cohort of free primary school children have begun enrolling in university studies.

Nonetheless, much progress in educational quality and access remains to be made in Kenya. In 2010, one million children were still out of school, and while this was almost half the number in 1999, it is still the ninth highest of any country in the world. Issues related to educational quality persist, especially at the primary level, with illiteracy rates increasing among students with six years of primary schooling. Over a quarter of young people have less than a lower secondary education and one in ten did not complete primary school.

At the university level, student numbers grew by a massive 28 percent between 2013 and 2014 and similar growth is expected this year, yet funding was cut by 6 percent in the 2015 national budget. The mismatch between funding and enrollment growth will mean a heavier tuition burden for students, increasing the significant access issues that already exist for the marginalized, and adding to quality issues related to overcrowding, overburdened infrastructure and faculty shortages.

WENR-0615-CountryProfile-Kenya-v2

International Mobility

According to UNESCO data, there were 13,573 Kenyan students studying abroad in 2012, with 3,776 in the United States, 2,235 in the UK and 1,191 in Australia. These numbers have been declining significantly over the last decade.

The United States hosted just 3,500 Kenyans last year as compared to a high of 7,800 in 2003. The decline, which has been particularly precipitous at the undergraduate level, has been attributed to the tightening of visa policies in the post 9/11 era and the considerable expense of a Western education when compared to cheaper alternatives in neighboring East African countries. The number of Kenyans coming to the U.S. for a graduate education has declined significantly less, indicative of the generally poor opportunities for research degrees at Kenyan universities and the widening of domestic access at the undergraduate level.

While not captured in the UNESCO data, local Kenyan media reports suggest that the vast majority of internationally mobile Kenyan students are in neighboring countries. More than 20,000 Kenyan students are estimated to be studying in Ugandan universities, and approximately 5,000 in Tanzania.

Kenya-Student-Mobility-to-the-US-2000-2015

Education System

Kenya’s national education system is structured on an 8-4-4 model with eight years of basic education, four years of secondary education and a four-year undergraduate curriculum. This model replaced the 7-4-2-3 system in 1985.

Formal schooling begins at the age of six, with compulsory and free basic education running through to the age of 14. Students progress to the academic secondary cycle, technical schools or trade schools from the basic cycle. Secondary schooling is also free but not compulsory.

Basic Education

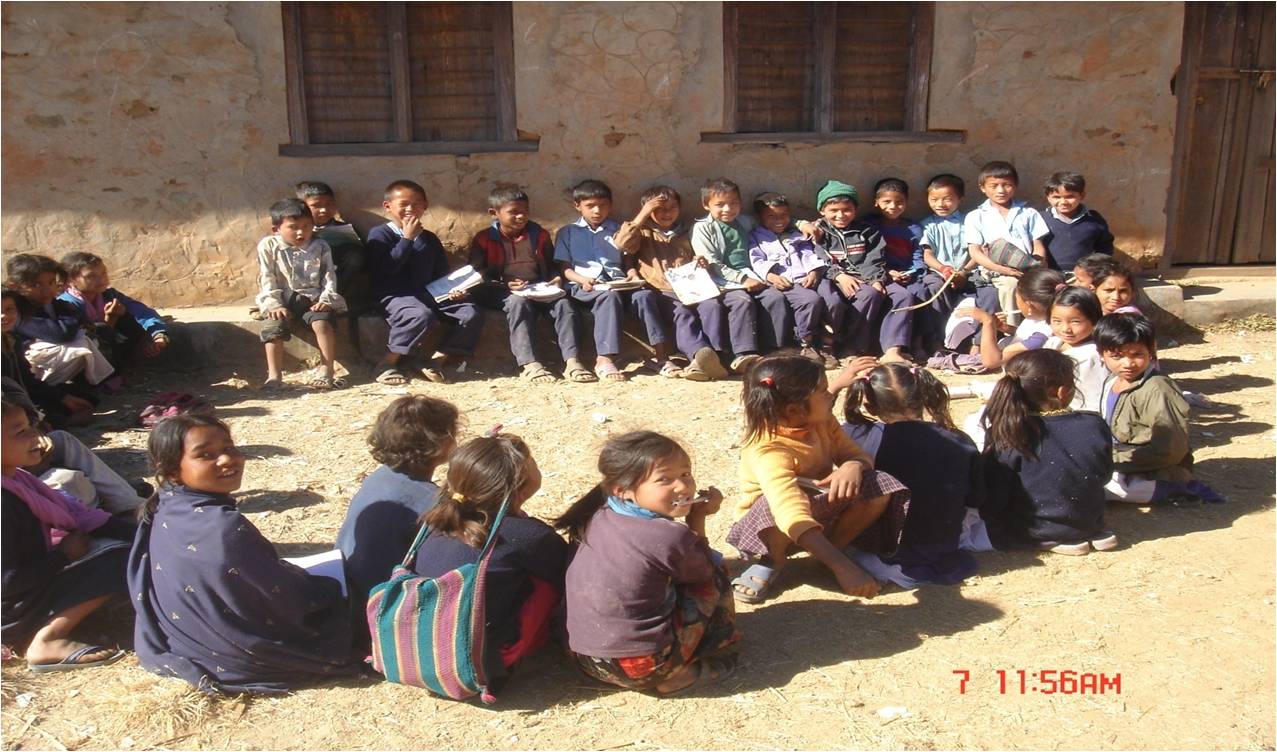

Primary education was made free to all students in 2003, a policy that increased attendance by almost 40 percent within four years, from 5.9 million in 2003 to 8.2 million in 2007.

The cycle is divided into lower (Standards 1-3), middle (Standards 4 & 5) and upper primary (Standards 6-8). At the end of the primary cycle, students take the national Kenya Certificate of Primary Education examination (KCPE), supervised by the Kenya National Examination Council (KNEC) under the Ministry of Education. The examination is used primarily to rank and stream students into secondary and technical schools. Students who perform well gain admission into national secondary schools, while those with average scores attend provincial schools.

The curriculum is uniform across the country and includes: English, Kiswahili, a local language, mathematics, science, social studies, religious education, creative arts, physical education, and life skills. Exams are held in five subjects: Kiswahili, English, mathematics, science and agriculture, and social studies.

Secondary Education

The secondary cycle lasts four years and is organized into two, two-year stages. At the end of the fourth year, students take examinations administered by the KNEC, which lead to the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE). The examination is also used for admissions into universities and training at other institutions of higher education in the technical and vocational stream.

Holders of the KCPE who do not enroll in secondary schools can attend youth polytechnics, which prepare students for Government Trade Tests, levels 1–3. Less than 50 percent of primary school students continue on to secondary school.

There are three types of secondary schools in Kenya – public, private and harambe. Students with the best scores on the KCPE attend national public schools, while lower scoring students tend to attend provincial and district level schools. Harambee schools do not receive full funding from the government and are run by local communities. These schools tend to be less selective than public schools.

Many private schools have religious affiliations and typically offer British or – less frequently – American curriculums and qualifications. Many also offer the Kenyan curriculum. Non-formal education centers provide basic education for children who are unable to access formal education, especially in impoverished urban and rural areas.

Students who fail examinations either repeat the final school year or pursue technical and vocational education, either at four-year technical secondary schools or three- to five-year trade schools. Since 2010, graduates of technical secondary schools are eligible for university entry.

Thirty subjects are currently offered at the academic secondary level, grouped into six learning areas:

Languages (English, Kiswahili, Arabic, German, French)

Sciences (mathematics, chemistry, physics, biology)

Applied Sciences (home science, agriculture, computer studies)

Humanities (history, geography, religious education, life skills, business studies)

Creative Arts (music, art and design)

Technical Subjects (drawing and design, building construction, power and mechanics, metal work, aviation, woodwork, electronics)

In the first two years of secondary education, students take as many as 13 subjects. This is narrowed down to eight subjects in the final two years, with three core and compulsory subjects taken by all students: English, Kiswahili and Mathematics. Students must also take two science subjects, one humanities subject, either one applied science or one technical subject chosen from the pool of subjects above. The subjects offered will depend on individual schools and what they can offer in terms of learning resources and teachers.

Students are tested in four subject groups for the KCSE school leaving examination. The three subjects in Group 1 (English, Kiswahili and mathematics) are compulsory. The final grade on the KCSE is an average of the scores achieved in the best eight subject examinations. Where a candidate sits for more than eight subjects, the average grade is based on the best eight scores. A final grade of C+ is required for university entry, although higher scores are required for some public universities. Admission to programs leading to certificates and diplomas at polytechnics requires a D+ or C- average, respectively.

Kenya-Secondary-Grading-Scale-with-US-Equivalency

English is the language of instruction in all secondary schools. Kiswahili is taught along with other subjects.

Higher Education

In recent years there has been a huge expansion of the higher education sector in Kenya. Where there were just five public universities in the country in 2005, today there are 22 with plans for as many as 20 new universities. Growth in the university sector has largely come about through the upgrade of already existing colleges. In addition, there are 17 private universities and 14 public and private university constituent colleges. An additional 14 institutions have letters of interim authority to operate. All of the above have the authority to award academic degrees.

Along with growth in the number of universities has come huge growth in enrollments. The latest enrollment figures for 2014 show that there were 443,783 students enrolled at universities across Kenya, more than double the 2012 enrollment number. Approximately 215,000 of those students were enrolled at private institutions.

In the non-university sector, students attend public and private technical and vocational polytechnics, colleges (teacher and medical colleges), and other tertiary-level TVET institutions (technical training institutes, institutes of technology, and technical and professional colleges). Typically, programs offered at these institutions are two to three years in length, leading to certificates, diplomas and higher national diplomas.

Current government plans call for the establishment of at least 20 new public universities, many in underserved regions, but recent budget cuts now call those plans into question. Meanwhile, lecturer shortages continue to hinder growth in quality standards and lead to ever growing student to faculty ratios.

Administrative control related tasks and management responsibilities are shared among the central (national) government, local (county and district level) authorities and the education institutions. Overall responsibility lies with the Ministry of Human Resources, which is in charge of education, culture, social affairs, health care, youth and sport. However, school-based VET and adult training is within the competence of the Ministry for National Economy.

Administrative control related tasks and management responsibilities are shared among the central (national) government, local (county and district level) authorities and the education institutions. Overall responsibility lies with the Ministry of Human Resources, which is in charge of education, culture, social affairs, health care, youth and sport. However, school-based VET and adult training is within the competence of the Ministry for National Economy.